University of Mississippi engineers will soon conduct preclinical testing on an implantable device that microdoses LSD and other psychoactive drugs to combat treatment-resistant depression.

Thomas Werfel, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, and Glenn Walker, professor of biomedical engineering, have launched Interval Therapeutics LLC to bring the three-year project into the next stage of development. The project recently received state funding from the Strengthening Mississippi Academic Research Through Business Act.

Therapy options are limited for individuals with treatment-resistant depression. One approach involves waiting a longer period for an antidepressant to become effective, and another includes adding additional drugs to the patient's regimen. Both are burdensome to the patient.

As a possible alternative, microdosing involves taking a small-enough amount of a psychoactive drug that it does not cause hallucinations. Repetitive microdosing of drugs such as LSD and psilocybin have been reported to have surprising benefits.

A prime challenge of administering psychoactive drugs, however, is the potential for abuse. In 2020, Werfel and Walker set out to answer the question of how exactly to deliver these drugs so that they cannot be abused or diverted.

"Our device is a fully biodegradable and implantable – and it ensures that the drug gets delivered when it's supposed to be," Werfel said. "The goal is to implant a very small device, and it microdoses the psychedelic every three to five days for a length of time. Then, it erodes into the body, eliminating the need to retrieve the device."

Walker's background is in microfabrication. He was intrigued when Werfel initially approached him about the project.

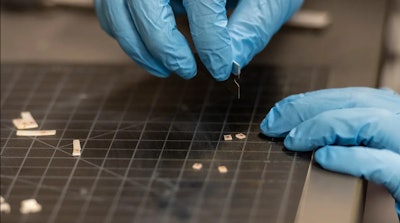

"We got to talking, and I told him about some cool techniques we could use to build a new kind of drug delivery device," Walker said. "I use tools that are typically used in the semiconductor sensor industry and apply them to biomedical problems instead. Microfabrication opens up all sorts of interesting possibilities for administering drugs that haven't been explored before."

The device is about the size of a grain of rice, Walker said. That makes it easily injected under the skin, where it periodically delivers a drug and dissolves when done.

"The really exciting thing about the device is that you could apply it to all sorts of different diseases," he said. "Anything that requires repeated application of a dose: heart medication, diabetes, you name it. We're targeting depression initially, but we expect other applications will emerge. In theory, you could go to the doctor, get an injection and your medicine is taken care of for the entire month or more."

Werfel and Walker are in the process of securing funding for their company to conduct advanced preclinical testing on the device. The ultimate goal is to obtain Investigational New Drug status from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for human clinical trials, although this could take several years.